Forbidden City of Beijing

It is the most worthwhile attraction to visit in Beijing.

We’re going to explain why the China Forbidden City (故宫) is worth visiting, what specific attractions it has, and the value behind each one. At the end, we’ll also include some Q&A and ticket info.

We believe a historical building isn’t just a structure—it’s a place where people once lived. The stories those people left behind are what make visiting the building meaningful.

Our goal is to explain the Chinese culture and stories within the Forbidden City in a simple, easy-to-understand way. Of course, we won’t get too wordy—after all, this is an article about “visiting the Forbidden City.” If you’re interested in any specific details, feel free to dig deeper on your own.

Table of Contents

Why the Forbidden City is Worth Visiting

1. It's the pinnacle of ancient Chinese architectural art!

How big is the Beijing Forbidden City? Well, it took 100,000 workers 14 years to complete. It covers about 720,000 square meters, which is equivalent to 101 standard football fields. But it’s not the largest palace in the world—that title goes to the Palace of Versailles in Paris. The Forbidden City ranks second. However, Versailles only covers 110,000 square meters, while the Forbidden City’s buildings span 150,000 square meters. For China, the Forbidden City represents the highest level of traditional architecture—there’s nothing else like it. From the walls, eaves, and stairs, to the doors, windows, and furniture, every detail is a masterpiece of traditional Chinese craftsmanship. If you look closely, you’ll find not a single screw in the whole palace. With over 9,000 rooms, all made of wood, none of them use any screws. You might think a building without screws would be unstable, but these buildings use the traditional Chinese “mortise and tenon” technique, which makes them strong enough to withstand a magnitude 10 earthquake.

2. Experience the most luxurious ancient Chinese living conditions up close.

The Forbidden City Peking wasn’t just where the emperor worked; it was also where he lived with his wives and children. In ancient China, there was a saying: “All the land under heaven belongs to the emperor.” This meant that the emperor was the ruler of all the people and lands in the empire. So, you can imagine how luxurious his living space must have been. Here, you can visit the emperor’s sleeping quarters, the “Qianqing Palace,” his banquet hall, the “Taihe Hall,” and his private garden, the “Imperial Garden,” among others. Of course, the Forbidden City wasn’t just the emperor’s home; it was also where servants and guards lived and worked. Every palace and courtyard here holds its own little-known, mysterious stories.

Do you know how many wives and children the emperors of the Qing Dynasty had? The third emperor, Shunzhi (顺治), had 19 wives and 14 children. The fourth emperor, Kangxi (康熙), had 62 wives and 55 children. The fifth emperor, Yongzheng (雍正), had 28 wives and 14 children.

3. Learn how this ancient civilization managed a population of hundreds of millions during the feudal era.

The Forbidden City Beijing was the royal palace of China’s last two dynasties: the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911). It was home to 24 emperors and served as the center of political power during China’s feudal period. In the Ming dynasty, China had about 200 million people, and by the Qing dynasty, the population had grown to around 430 million. The heart of this vast empire, which managed such a large population, was the Forbidden City.

During the Qing dynasty, Beijing had various departments responsible for the military, law, finance, construction, and ceremonies. All these departments answered directly to the emperor. Every ten days, officials would enter the Forbidden City Palace to report to the emperor in a process called “Morning Court.” At these sessions, officials would update the emperor on important national matters or any pressing issues. However, only major issues were discussed in the court; minor matters were submitted in writing for the emperor’s review and feedback.

If you want to learn more about how the emperors ruled China, visiting the Forbidden City is definitely the best way to do it.

Main Attractions of the Forbidden City

Meridian Gate (午门)

The Meridian Gate is the main entrance to the Peking Forbidden City, but only the emperor could use it. No one else was allowed to pass through this gate. There were two exceptions: first, when the emperor got married, the empress could enter through it, but only for that occasion; second, when the country held civil service exams, the top three winners could walk out through this gate after meeting the emperor. This shows that the Meridian Gate was a symbol of the emperor’s authority, with strict rules even for his own wife.

Golden Water Bridge (金水桥)

After passing through the Meridian Gate, you’ll see five stone bridges called the Golden Water Bridge. Below them is the only river inside the Forbidden City, used for daily water supply and firefighting. These five bridges follow a strict hierarchy. The central bridge, called the Emperor’s Bridge (御路桥), was for the emperor only. The bridges on either side of it were for the emperor’s relatives. The outermost two bridges were reserved for high-ranking officials. As for lower-ranking officials? They had to walk around the outer edge of the square to pass through. If they accidentally took the wrong bridge, they could be executed by the emperor.

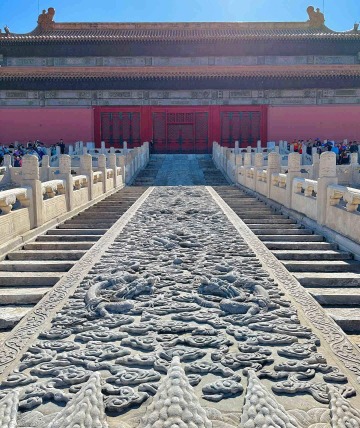

Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿)

Walk past the Golden Water Bridge, and you’ll reach the largest palace in the Forbidden City, the Hall of Supreme Harmony. This is where the emperor held major ceremonies like his coronation, weddings, military send-offs, and birthday banquets. The pillars inside are made of golden silk nanmu wood, and the carpets are woven from wool and silk. In the center of the hall sits the emperor’s throne, with 13 golden dragons carved into the backrest—super luxurious.

If you’ve seen the movie The Last Emperor, you’ll know that China’s last emperor, Pu Yi (溥仪), was only three years old when he took the throne. Can you imagine a three-year-old ruling over a country of 430 million people? In 1908, Pu Yi’s coronation ceremony was held here in the Hall of Supreme Harmony. The young emperor cried during the ceremony, symbolizing the sad end of the Qing Dynasty.

Hall of Central Harmony (中和殿)

After the Hall of Supreme Harmony, you’ll come to the Hall of Central Harmony. You can think of it like the “backstage” before a big speech. It was the emperor’s resting spot before major ceremonies. Here, he’d fix his robes, review the ceremony steps, and mentally prepare for what was about to happen.

Hall of Preserving Harmony (保和殿)

Back in the Qing Dynasty, if you wanted to become an official, you had to pass the national exam, known as the Keju (科举). The final exam (the big one) was held in the Hall of Preserving Harmony in the Forbidden City. But this exam only took place every three years. Most of the time, the hall was used for banquets during special occasions. It was also the residence of the third and fourth emperors of the Qing Dynasty.

The idea of selecting officials through a fair, nationwide exam started back in 605 AD. Before that, China mainly used hereditary positions or recommendations from senior officials, which made it nearly impossible for ordinary people to rise to the top. The Keju system not only improved the quality of officials but also gave common people a shot at becoming government workers. But over time, the exam questions became rigid and outdated, which stifled the country’s thinking and made it harder for society and technology to move forward.

Hall of Supreme Purity (乾清宫)

After passing through the Hall of Preserving Harmony, you enter the residential area. The Hall of Supreme Purity was home to 16 emperors. But it wasn’t just a place for sleeping – it was also where the emperor did his work, much like how many people set up a study at home for reading and working. On a daily basis, the emperor would read letters from officials, discuss matters with his cabinet, and meet with officials for private reports.

You might think being an emperor sounds like a life of luxury, but you’d be completely wrong. The life of a Qing emperor was anything but easy. They usually woke up around 4 or 5 in the morning. After greeting their elders, they’d start with morning reading and breakfast. Then came listening to officials’ reports and reviewing documents, a schedule that lasted well into the night. This was pretty much their routine every day.

The Palace of Earthly Tranquility (坤宁宫)

After visiting the emperor’s rooms, the next stop is the empress’s residence—the Palace of Earthly Tranquility. During festivals, the emperor’s children and his lower-ranking wives would come here to greet the empress. After the fifth emperor of the Qing Dynasty, the empress no longer lived here, and the palace was repurposed as a site for Shamanist rituals.

In ancient Chinese royal families, the emperor’s wives were ranked in several tiers. In the Qing Dynasty, there were eight ranks, with the empress being the highest and the only one of her rank. Every three years, a selection process was held to choose women who could become the emperor’s wives. These women had to undergo strict screening based on their background, age, and other factors. Only after all the checks would the emperor, along with his mother, personally select the women who would become his wives and assign them their titles.

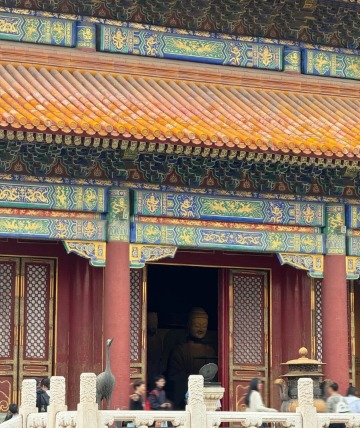

The Palace of Compassion and Tranquility (慈宁宫)

The Palace of Compassion and Tranquility was the residence of the emperor’s mother. The most famous occupant was Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang (孝庄太后), the first to live here for 44 years. She was an outstanding politician, having assisted two Qing emperors: Shunzhi and Kangxi. Shunzhi became emperor at just 6 years old, and Kangxi at 8. Without Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, the royal family would have faced serious troubles.

The palace also housed a Buddhist hall, where religious activities like chanting and prayers for blessings were held. This reflected the deep respect the imperial family had for Buddhism at the time. There’s even a legend that Emperor Shunzhi eventually left the throne to become a monk.

The Gate of Divine Prowess (神武门)

The Gate of Divine Prowess is the back gate of the China Forbidden City (Gu Gong). Many significant historical events occurred here, including the escape of the last Ming emperor, Chongzhen (崇祯), who fled through this gate, marking the end of the Ming Dynasty. The last Qing emperor, Puyi, was also driven out of the Forbidden City Palace through this gate. In a way, the fall of both the Ming and Qing dynasties is closely linked to the Gate of Divine Prowess.

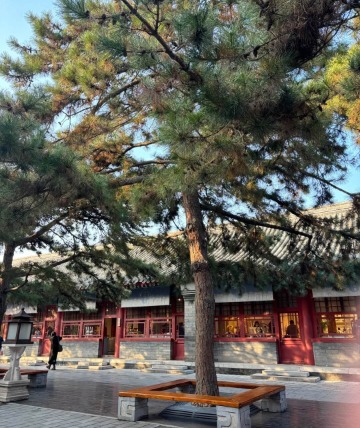

The Imperial Garden (御花园)

The Imperial Garden was a place where the emperor and his family would stroll and relax, covering an area about the size of 1.68 football fields. As a royal garden, its design is truly exquisite. The garden features a variety of stone lions and sculptures, along with ancient pavilions for shade. Scattered throughout are over 160 ancient trees and a range of beautiful bonsai plants. It’s fair to say that this garden is a top example of traditional Chinese landscaping at its finest.

Exhibitions at the Beijing Palace

The Treasure Gallery (珍宝馆)

As soon as you enter, you’ll see a striking, colorful wall – the Nine-Dragon Wall. Made of glazed tiles, it features nine three-dimensional dragons. These lifelike dragons symbolize the grandeur and authority of the imperial family. Beyond the Nine-Dragon Wall, you’ll enter the main exhibition area, which includes sections on jewelry, gold and silverware, jade, and bonsai.

The most famous item here is the Phoenix Crown of Empress Dowager Xiaojing (which is also quite popular on Chinese social media for its exquisite design). The crown is adorned with 34 sapphires, 59 rubies, and over 3,000 natural pearls—it’s incredibly luxurious. What makes it especially unique is the use of kingfisher feathers. Under different lighting, the crown shifts in shades of blue, and if you get close enough, you can even see the texture of the feathers. You might be surprised to learn that this dazzling crown was never actually worn by its owner. Empress Dowager Xiaojing was only posthumously named empress after her grandson became emperor, by which time she had already passed away.

In addition to the Phoenix Crown, the Treasure Gallery has many other beautiful treasures, mostly consisting of royal jewelry and ornamental pieces.

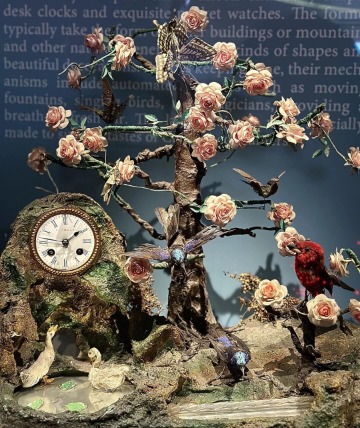

The Clock Gallery (钟表馆)

Most of the items in the Clock Gallery are part of the imperial collection. The gallery holds around 1,500 clocks, many of which were collected by Emperor Qianlong (乾隆). In fact, the collection was much larger in Qianlong’s time. Back then, nearly every corner of the Beijing Palace was filled with clocks, and the ticking sound of these timepieces echoed throughout the palace.

FAQ About the China Forbidden City

1. When was the Forbidden City built?

The construction of the Forbidden City began during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Work started in 1406 and was completed in 1420. Initially, the Ming capital was not in Beijing but in Nanjing, where you can still find the Nanjing Forbidden City today. It was only when the third Ming emperor, Zhu Di (朱棣), moved the capital to Beijing that the current Forbidden City of China was built.

The reason for relocating the capital to Beijing was mainly to be closer to the northern borders. From a strategic standpoint, Beijing was more accessible to the frontier military, which made it easier to manage and defend against invasions, particularly from the Mongols in the north.

2. Who built the Forbidden City?

The Forbidden City was ordered to be built by the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty, Emperor Zhu Di. The chief architect behind its design was the famous Ming architect Kuai Xiang (蒯祥), who is credited with making the Forbidden City (Gu Gong) a grand, solid, and artistically impressive palace.

3. Where is the Forbidden City located?

This question might seem easy to answer—of course, it’s in Beijing. But actually, besides the Forbidden City in Beijing, there are also the Nanjing Forbidden City and the Shenyang Forbidden City.

The Shenyang Forbidden City was the palace of the early Qing Dynasty. It wasn’t until the third Qing emperor moved the capital to Beijing that the Beijing Forbidden City became the main imperial residence.

The Taipei Forbidden City came into existence because, in the first half of the 20th century, China went through long periods of war and political instability, especially during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War. Many priceless artifacts from the Beijing Forbidden City were at risk of being damaged or lost. To protect these treasures, the Nationalist government moved part of the collection to Taiwan. After the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan in 1949, a large number of artifacts from the Beijing Forbidden City were also relocated there.

4. What is the Chinese name of the Forbidden City?

The Forbidden City’s Chinese name is “故宫” (Gùgōng) or “紫禁城” (Zǐjìnchéng), and it is also called the “Forbidden City Palace Museum” (故宫博物院 Gùgōng Bówùyuàn), all referring to the same place. From its name, you can tell that the Forbidden City China is not just a vast collection of ancient Chinese architecture—it is also home to China’s largest museum, with over 1.8 million artifacts in its collection.

5. Why is it called the Forbidden City?

The Chinese name for the Forbidden City of Beijing is “紫禁城”, which literally translates to “Purple” (紫), “Forbidden” (禁), and “City” (城). In ancient Chinese culture, purple was a color associated with royalty, representing nobility, power, and mystery. Only the emperor and his family were allowed to use this color.

As the emperor’s residence, the Forbidden City was a highly restricted area, off-limits to ordinary people. It was a place that was closed off from the outside world. So, the full meaning of the name “Forbidden City” refers to “A royal palace, a noble and restricted place where common people are forbidden to enter.”

How to get to the Forbidden City

I recommend taking the subway.

- Take Line 1 and get off at Tian’anmen East Station (Exit B). Walk across Tiananmen Square, go through security, and you’ll be at the entrance to the Beijing Palace.

- You can also take Line 8, get off at Jinyu Hutong Station (Exit C), turn right, and walk straight to Donghua Gate. Then, follow the red walls of the Gu Gong to Meridian Gate.

Hours & Fees

Hours

Daily from 8:30 AM to 5:00 PM (last entry at 4:00 PM). Closed every Monday.

Time Required

6-8 hours.

Fees

60 CNY (about 8 USD) per person.

Practical Tips

I recommend visiting the Forbidden City (Beijing Palace), Tian’anmen Square, and Jingshan Park together. Jingshan Park is right outside Shenwu Gate. It’s the highest point in the city center, offering a great view of the Forbidden City as well as other landmarks like the Drum Tower, Belltower, and Olympic Tower.

Tickets for the Forbidden City are hard to get, so I suggest trying to book them 7 days in advance. Avoid visiting during Chinese holidays if you can, because tickets will sell out quickly, and there will be huge crowds.

You can rent an audio guide at the entrance, with several languages to choose from. The guide will automatically provide information about each site as you explore.